3 July 2020 – 2 October 2020

This Exhibition Is Untitled

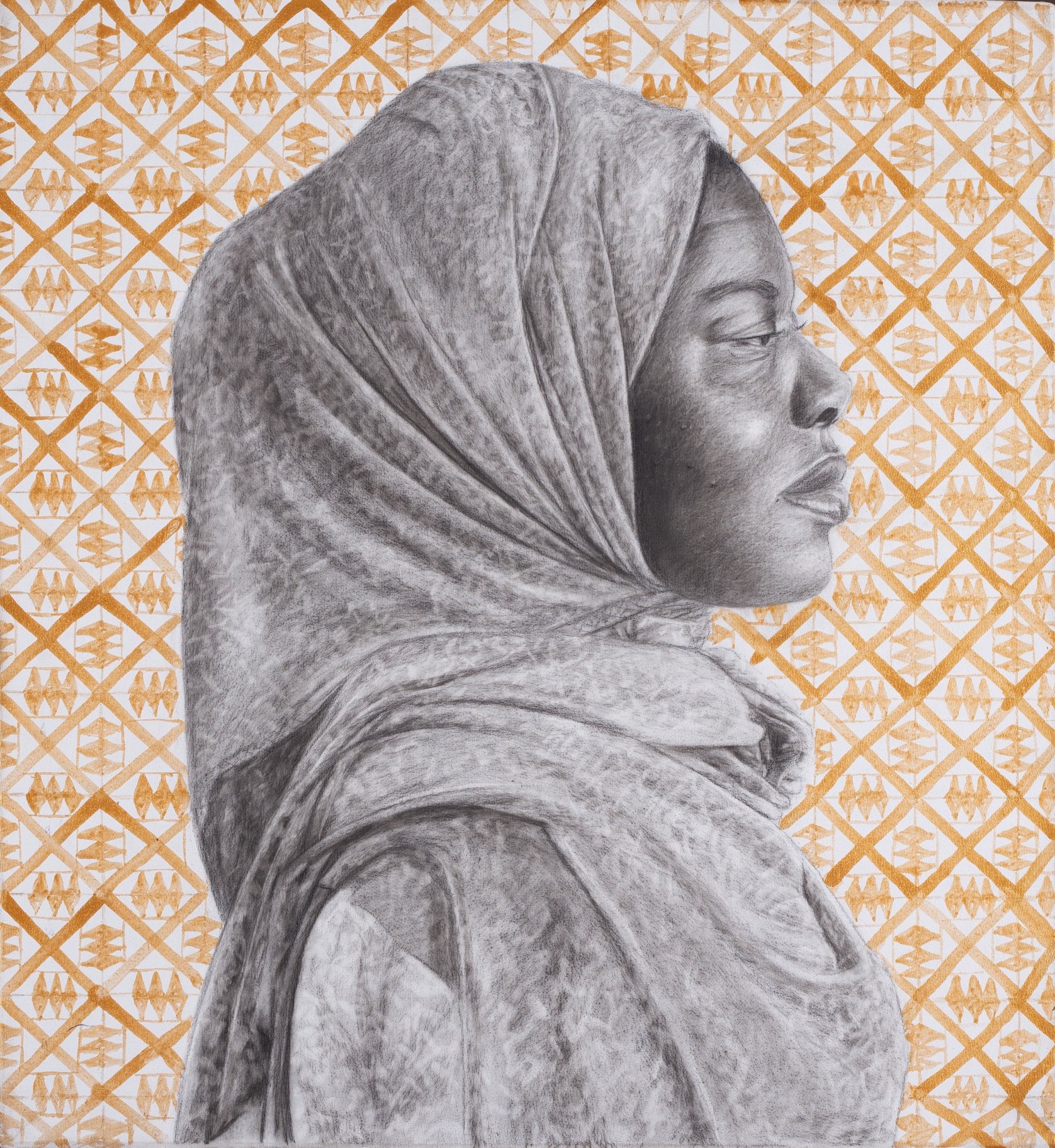

Musah Yusif

Rufai Zakari

Winfred Nana Amoah

Bernice Ameyaw

The 89plus project was launched in 2013 to project the generation of artists born in or after 1989. Suggesting a correlation between significant world-changing events and increased creative production, the project brief noted ‘the year 1989 saw the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the start of the post- Cold War period, and the introduction of the World Wide Web and the beginning of the universal availability of the Internet’1.

In 1989 Ghana, the political and economic conditions were changing. Ghana was emerging from the 1982/3 famine and the subsequent Structural Adjustment Program which consolidated the neoliberalist agenda of the Bretton Woods institutions. The country was also adjusting to the September 1989 coup attempt and a ban on Christian groups including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Jehovah Witnesses. Two years earlier, History professorAlbert Adu Boahen had broken the so-called ‘culture of silence’, an agitation that together with others, culminated into the 1992 elections. Globally, 1989 was a significant year.

The artists featured in THIS EXHBITION IS UNTITLED come from the generation that the 89plus project focused on. Far from offering a definition of what this generation is grappling with, the exhibition suggests a snapshot of the artist’s trajectory beginnings. Using the material conditions of neoliberalism, globalisation and consumerism including plastics, wax prints, call credit cards, hair, bitumen and disused everyday objects, the artists featured in this exhibition confront the failures of modernism.

If we are to believe Terry Smith2, contemporaneity is a relational aesthetic comprising refashioning modernism, engaging the conditions of the present and the pluralities of the present and the future.

European modernism built on the idea that the artist is a genius. Elsewhere in the imperial project, practitioners were stripped of the ‘artist’ title and the colonial schools taught art by ‘hand and eye’. The practitioner was called a ‘craft (wo)man’ and the trained artist, devoid of engaging with the creative process.

In 1989 Ghana, the political and economic conditions were changing. Ghana was emerging from the 1982/3 famine and the subsequent Structural Adjustment Program which consolidated the neoliberalist agenda of the Bretton Woods institutions. The country was also adjusting to the September 1989 coup attempt and a ban on Christian groups including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Jehovah Witnesses. Two years earlier, History professorAlbert Adu Boahen had broken the so-called ‘culture of silence’, an agitation that together with others, culminated into the 1992 elections. Globally, 1989 was a significant year.

The artists featured in THIS EXHBITION IS UNTITLED come from the generation that the 89plus project focused on. Far from offering a definition of what this generation is grappling with, the exhibition suggests a snapshot of the artist’s trajectory beginnings. Using the material conditions of neoliberalism, globalisation and consumerism including plastics, wax prints, call credit cards, hair, bitumen and disused everyday objects, the artists featured in this exhibition confront the failures of modernism.

If we are to believe Terry Smith2, contemporaneity is a relational aesthetic comprising refashioning modernism, engaging the conditions of the present and the pluralities of the present and the future.

European modernism built on the idea that the artist is a genius. Elsewhere in the imperial project, practitioners were stripped of the ‘artist’ title and the colonial schools taught art by ‘hand and eye’. The practitioner was called a ‘craft (wo)man’ and the trained artist, devoid of engaging with the creative process.

Rosemary Esinam Damalie’s handwoven hair sculptures participate in the notion of the ‘myth of the artist’ (markedly different from Jennifer T. Soong’s3 use of the term to mean ‘believing the artist’). Their confrontation with art histories is to pose the question: What is craft? When and how does a craft become an art?

The power is that Damalie uses the colonial pedagogy of ‘hand and eye’– weaving – to question the Western colonialist rendition of art and its histories.

Confronting the present, Yussif Musah’s larger-than-life self-portraits wrestle with death or the idea of it. In a politically charged world where black boys and girls are lynched every day, Yussif manages to capture the anxiety of living as a black person with no evidence of violence. In a sense, he escapes the stern criticism of Teju Cole’s opening lines of his 2015 essay, Death in the Browser4:

‘There you are watching another death on video. In the course of ordinary life — at lunch or in bed, in a car or in the park — you are suddenly plunged into someone else’s crisis, someone else’s horror’.

Musah’s self-portrait scenes merge the documented (from the public archive/ memory such as books and dreams) and the speculated (through play). The performance of the death anxiety is one that is euphemismised with picking of flowers, vulture attack and human skeletons.

Bernice Ameyaw’s installations thrive on gathering and fabricating disused objects. In the time of COVID-19 when we are physically distancing, the idea of gathering remains ever pertinent. By not gathering, we lose the shape and rhythm of our communities. Even at the risk of being mundane, the hope is that gatherings will become possible (again). Both Amoah and Zakari’s practice of collecting ‘waste’ materials and collaging them into figurations remind us of the lives that we have lived previously and those that we hope to live later. Zakari’s woman figurations exist with such carelessness, and sassiness, and transgression. Amoah, on the other hand, focuses on the face area that in real life is now inhabited by facemasks.

Regardless of the artist’s practice, the gallery offers the space for each of the works to be viewed in the presence of the others – in relation to the others- the present and absent. To put it in the words of Martinique writer and philosopher Edouard Glissant, the Whole-world is ‘the realised totality of the known and unknown data of our worlds’ including “all sudden presences, as well as all times and spaces of the world’s peoples”5. We should think of art contemporaneity as such.

The power is that Damalie uses the colonial pedagogy of ‘hand and eye’– weaving – to question the Western colonialist rendition of art and its histories.

Confronting the present, Yussif Musah’s larger-than-life self-portraits wrestle with death or the idea of it. In a politically charged world where black boys and girls are lynched every day, Yussif manages to capture the anxiety of living as a black person with no evidence of violence. In a sense, he escapes the stern criticism of Teju Cole’s opening lines of his 2015 essay, Death in the Browser4:

‘There you are watching another death on video. In the course of ordinary life — at lunch or in bed, in a car or in the park — you are suddenly plunged into someone else’s crisis, someone else’s horror’.

Musah’s self-portrait scenes merge the documented (from the public archive/ memory such as books and dreams) and the speculated (through play). The performance of the death anxiety is one that is euphemismised with picking of flowers, vulture attack and human skeletons.

Bernice Ameyaw’s installations thrive on gathering and fabricating disused objects. In the time of COVID-19 when we are physically distancing, the idea of gathering remains ever pertinent. By not gathering, we lose the shape and rhythm of our communities. Even at the risk of being mundane, the hope is that gatherings will become possible (again). Both Amoah and Zakari’s practice of collecting ‘waste’ materials and collaging them into figurations remind us of the lives that we have lived previously and those that we hope to live later. Zakari’s woman figurations exist with such carelessness, and sassiness, and transgression. Amoah, on the other hand, focuses on the face area that in real life is now inhabited by facemasks.

Regardless of the artist’s practice, the gallery offers the space for each of the works to be viewed in the presence of the others – in relation to the others- the present and absent. To put it in the words of Martinique writer and philosopher Edouard Glissant, the Whole-world is ‘the realised totality of the known and unknown data of our worlds’ including “all sudden presences, as well as all times and spaces of the world’s peoples”5. We should think of art contemporaneity as such.